Every year, there are at least several deaths in the United States from eating poisonous mushrooms. Most of these cases happen because of mistaken identity. The person who foraged the mushroom believed it to be something else and was certain enough of their identification to cook it up for the dinner table.

The most troubling and scary aspect of this is that not all mushrooms will make you sick or kill you straight away. There is a mistaken belief that if you’ve eaten a poisonous mushroom, it will kill you instantaneously. This is far from the truth! Many of the most poisonous mushrooms are sneaky with their toxins and may take up to even 2 weeks to show effects. And, often by that time, it is too late.

Before you forage and eat any wild mushroom, you must be 1000% sure of your identification. But mistakes do happen, and if you realize it in time, you can get the treatment you need.

This guide covers what to do if you think you’ve eaten a poisonous mushroom. It also covers some of the most common side effects of mushroom poisoning – they vary greatly by species, so if you’re concerned with any symptoms you’re having, read through them.

Wild mushrooms can contain toxins that are extremely harmful, even in small amounts. Some of the most dangerous wild mushrooms are Amanita phalloides (the death cap), destroying angel species, and the funeral bell mushroom (Galerina marginata). These mushrooms can look very similar to safe, edible ones, and cooking them does not remove the toxic compounds. Just recently, several people in California died after eating death cap mushrooms.

Before you eat any wild mushroom, you must be 150% sure of your identification. Never make assumptions; always double-check your findings in books, online groups, and with local experts. Don’t rely on just one or the other, either; always check several sources. These safeguards will reduce the chances of making mistakes. If you’ve ever eaten a poisonous mushroom by mistake, you know how important all these steps are!

Unmasking the 7 Deadliest Poisonous Mushroom Species in the US

Jump to:

What to Do If You Eat a Poisonous Mushroom

If you think you have eaten a poisonous mushroom, treat it as a medical emergency. Do not wait for symptoms to appear. Some of the most dangerous mushroom toxins, such as those found in death cap mushrooms (Amanita phalloides), can take 6 to 24 hours or longer to cause symptoms. Don’t be overruled by your own sense of pride.

Here’s a great story about overcoming pride and getting emergency care after a mistaken identity with the destroying angel – a very important lesson for everyone who forages mushrooms. And one about orellanine poisoning from mistakenly eating a toxic Cortinarius species.

Also, just because you’re not having symptoms, it doesn’t mean serious stuff isn’t happening internally. In many cases, after you’ve eaten a poisonous mushroom, severe liver damage may already be happening inside your body even when you don’t notice it.

Even if you feel fine at first, you still need medical help. Never rely on home remedies or myths, such as cooking the mushroom, tasting it, or waiting to see if you feel sick. Cooking does not destroy many mushroom toxins, and delaying care can make the symptoms much more dangerous after you’ve eaten a poisonous mushroom.

The most important thing to do is to contact Poison Control immediately or go to the nearest emergency room. In the United States, Poison Control can be reached at 1-800-222-1222. They can tell you exactly what to do next. If possible, bring the mushroom or clear photos of it to the hospital so experts can identify the species and choose the best treatment. Treatments also vary by mushroom species, so it is extremely important to bring the mushroom or photos to the doctor so they can determine the best course of action.

Young children are particularly vulnerable to mushroom poisoning because they may swallow larger amounts relative to their body size. Their organs are also still developing and weaker. If a child has eaten a poisonous mushroom, even a single bite, do not hesitate to seek immediate medical evaluation.

The hospital will monitor closely for delayed onset symptoms. They may run blood tests to check liver and kidney function, watch for signs of dehydration, and provide symptom relief as needed. Collecting any remaining mushroom pieces is especially important in these cases because identifying the species can influence treatment decisions.

It is also important not to try home remedies unless advised by a medical professional. Doing things like inducing vomiting or giving food or drink to counteract the toxin can sometimes make the situation worse after you’ve eaten a poisonous mushroom.

Common Symptoms of Mushroom Poisoning

Symptoms can begin minutes to hours after eating a mushroom, or 6–24 hours (or more) after eating it.

Stomach and digestive symptoms

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Severe stomach or abdominal pain

Nervous system symptoms

- Dizziness or confusion

- Trouble thinking clearly

- Hallucinations

- Headache

- Seizures (in severe cases)

Serious warning signs

- Extreme tiredness or weakness

- Yellowing of the skin or eyes (sign of liver damage)

- Dark urine, bloody urine, or very little urine

Important:

Not all cases of mushroom poisoning are obvious right away. With some species, symptoms are delayed. And this is particularly dangerous because you may not realize the cause or the best course of action. Maybe it was the shrimp at lunch, or you ate some old leftovers the day before. Nailing down the exact source of your symptoms can be really tricky. And, delayed mushroom poisoning symptoms are extremely dangerous because of this. Even more scary, the most toxic mushrooms are often the ones with delayed symptoms.

Some mushrooms produce compounds that affect the nervous system, leading to hallucinations, confusion, agitation, or changes in heart rate. These effects are usually separate from the deadly organ-damaging toxins and usually require a different type of treatment. For example, mushrooms containing psilocybin may lead to neurological effects. These are generally less life-threatening than amatoxin poisoning, but still might require medical evaluation.

How Do I Know If The Mushroom Is Poisonous

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to this question. The only true way to know if a mushroom is poisonous, edible, or non-toxic is to identify it. That‘s it. No rules of thumb apply to poisonous mushrooms – they can be any color and size, have gills, or not have gills, and grow on a tree or from the ground. Each species needs to be identified individually to know what it is and whether it is poisonous.

One of the hardest aspects of mushroom poisoning is that there are no reliable home tests to determine whether a mushroom is poisonous. Old rules like checking whether a mushroom turns a silver spoon black or cooking to change its color are myths and can be dangerous. Appearance, taste, smell, or color are unreliable indicators of safety. Even experienced mushroom foragers sometimes misidentify dangerous species.

This is, of course, not what most people want to hear. It would be great if there were some telltale sign from the universe that let us know whether the mushroom is poisonous. Unfortunately, that is not the case. Each species is its own unique being, and some have developed toxins and others have not.

Safe Steps For Trying New Wild Mushrooms

We highly recommend that, before you try any new mushroom, you save one or two specimens in a bag in the refrigerator. This way, if there is an issue, there are intact, fresh specimens to bring to the doctor or to photograph.

Even if you are completely certain it is an edible species, we can’t stress how important it is to do this. It’s a pretty awful feeling knowing you ate something you were sure about, but now feel sick, and don’t have any way to verify what you ate. Some mushrooms might make you sick even though they’re classified as great edibles. We know someone who has allergic reactions to lion’s mane, someone else who experiences digestive hell from shrimp of the woods, and someone who breaks out after eating chicken of the woods.

These examples aren’t poisonous mushrooms, per se; they aren’t toxic, but for some people, they do cause issues. It’s good practice, just to be on the safe side and do proper due diligence, to save a few fresh specimens for at least 3-4 days after eating a new-to-you wild mushroom.

Place the mushroom, or any remaining pieces, in a paper bag and keep it cool — do not use a plastic bag. Plastic bags trap moisture and cause the mushrooms to decay faster, which makes identification harder. At the very least, take clear photographs of the mushroom that show the cap, gills or pores underneath, and the stem. This is vital for assisting doctors and mycologists (mushroom experts) in identifying the species and figuring out which toxins might be involved.

This safety guide for foraging mushrooms is a great resource for newbies and a great reminder for more advanced foragers.

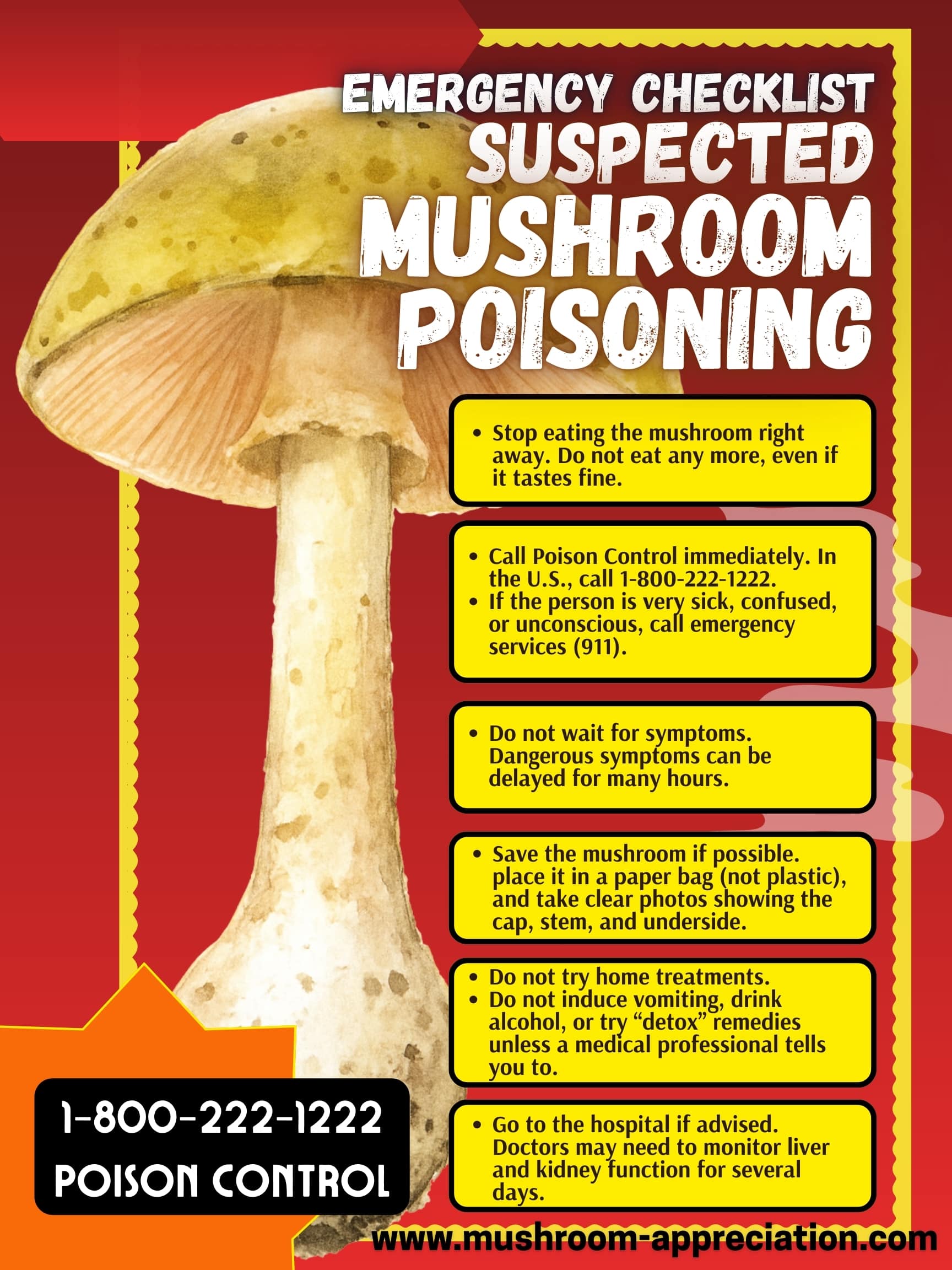

Emergency Checklist: Suspected Poisonous Mushroom Ingestion

If someone has eaten a wild or unknown mushroom, follow this checklist immediately:

- Stop eating the mushroom right away.

Do not eat any more, even if it tastes fine. - Call Poison Control immediately.

In the U.S., call 1-800-222-1222.

If the person is very sick, confused, or unconscious, call emergency services (911). - Do not wait for symptoms.

Dangerous symptoms can be delayed for many hours. - Save the mushroom if possible.

Place it in a paper bag (not plastic), or take clear photos showing the cap, stem, and underside. - Do not try home treatments.

Do not induce vomiting, drink alcohol, or try “detox” remedies unless a medical professional tells you to. - Go to the hospital if advised.

Doctors may need to monitor liver and kidney function for several days. - Watch for warning signs.

These include vomiting, diarrhea, stomach pain, confusion, dizziness, sweating, or extreme tiredness. - If a child ate a mushroom, act immediately.

Even a small bite can be dangerous for children.

Mushroom Toxins and Their Effects

| Toxin | Primary Effects / Symptoms | Mushrooms With This Toxin |

|---|---|---|

| Amatoxins (α-amanitin, β-amanitin) | Delayed onset (6–24 h); severe vomiting & diarrhea, often a deceptive “recovery” period after a few days → liver and kidney failure [more details on amatoxin poisoning] | Amanita phalloides (Death cap), A. virosa, Amanita bisporigera, Galerina marginata (funeral bell), Lepiota spp., Conocybe rugosa/ Pholiotina rugosa |

| Phallotoxins | GI irritation; damage to liver cells (less dangerous orally than amatoxins) | Same as amatoxin-containing Amanita species |

| Virotoxins | Similar to phallotoxins; contribute to liver damage | Amanita phalloides, A. virosa |

| Orellanine | Delayed kidney failure, can take 3 days to 3 weeks for symptoms to appear; thirst, decreased urination → irreversible kidney and liver damage | Cortinarius orellanus, C. rubellus |

| Muscarine | Excessive salivation, sweating, tears, slow heart rate, abdominal cramps – SLUDGE syndrome (usually not deadly but often need medical treatment) | Inocybe spp., Clitocybe dealbata, Clitocybe rivulosa, Omphalotus illudens, Omphalotus olivascens |

| Ibotenic acid & Muscimol | Confusion, hallucinations, sedation, muscle twitching | Amanita muscaria, A. pantherina |

| Gyromitrin (→ monomethylhydrazine) | Nausea, seizures, liver damage (has long term effects, rarely dangerous the first time you eat it) | Gyromitra esculenta (False morel) |

| Coprine | Alcohol intolerance: flushing, headache, nausea (with alcohol) (not deadly but will make you quite ill) | Coprinopsis atramentaria (Inky cap) |

| Psilocybin / Psilocin | Hallucinations, altered perception, anxiety, nausea | Psilocybe spp., Panaeolus spp., Gymnopilus spp. |

| Acromelic acids | Severe burning pain in hands & feet, lasting weeks | Clitocybe acromelalga |

| Unknown rhabdomyolysis toxin | Muscle breakdown, weakness, kidney injury | Tricholoma equestre (Yellow knight) [still being researched] |

| Immune-mediated hemolytic toxins | Destruction of red blood cells after repeated exposure | Paxillus involutus |

Leave a Reply