The prolific and widespread False Parasol (Chlorophyllum molybdites) is also known as the vomiter and with very good reason. If you make a mistake with this mushroom, you will regret it very quickly. This is the most eaten poisonous mushroom in North America, not on purpose, though, of course. The problem with the false parasol is that it looks very similar to several popular edible species.

To ensure you don’t make the mistake others have, read this guide thoroughly and make certain you understand the key identifying features. While it’s unlikely this mushroom will kill you, the extreme gastrointestinal distress is not something you want to experience.

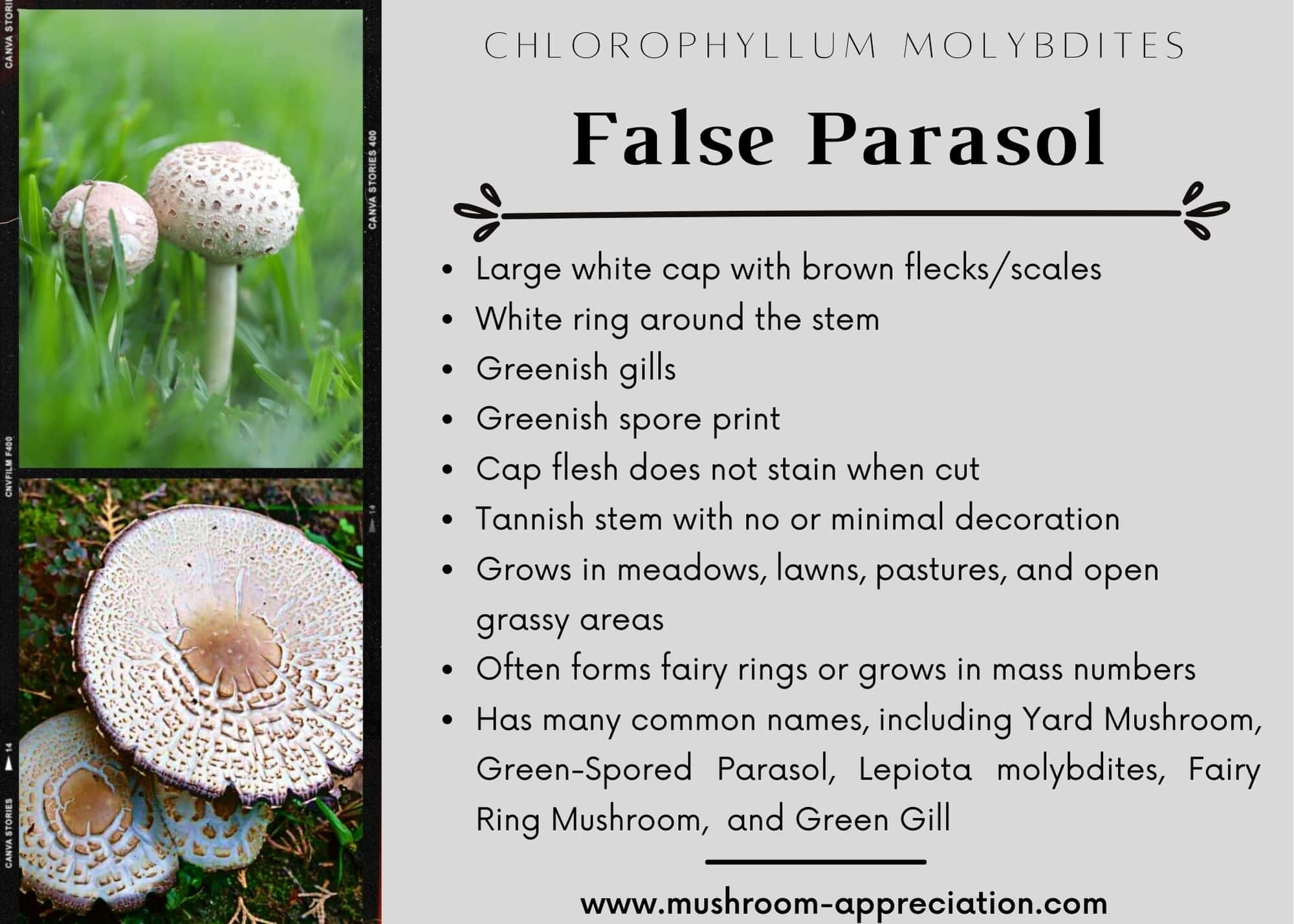

Chlorophyllum molybdites is also known as the False Parasol, Green-Spored Parasol, Lepiota molybdites, Fairy Ring Mushroom, Yard Mushroom, and Green Gill. False parasol is the most used common name, so that’s what we’ll use here.

Jump to:

Why So Many Poisonings From The False Parasol?

The false parasol causes tons of poisonings across North America for a number of reasons. Children and pets are especially at risk of poisoning from this mushroom, so it’s imperative that everyone know what it looks like and how to identify it.

The good news is that this mushroom isn’t likely to kill you as its toxin isn’t fatal, but unchecked will cause severe distress. Again, the threat is worse with children and pets due to their small size.

If you suspect poisoning from the false parasol or any mushroom, contact poison control immediately – (800) 222-1222 (people) or (888) 426-4435 (animals)

The reasons why the false parasol causes so many poisoning events:

- This mushroom is widespread across North America; it is very common in late summer and fall.

- It grows on lawns, in meadows and pastures, and landscaped areas, making them more likely to be seen and picked than forest-centered species, especially by children.

- They look incredibly similar to the true Parasol Mushroom (Macrolepiota procera) and Shaggy Parasol Mushroom (Chlorophyllum rhacodes), both of which are excellent edible species.

- They look very similar to Shaggy Mane mushrooms (Coprinus comatus), which are an edible species.

- They often grow in large groups or big fairy rings on the lawn, making them very visible and attractive (irresistible…) to some people.

All About The False Parasol

The false parasol mushroom grows across North America, but is uncommon in the Pacific Northwest (it does still appear there, though). It is more common on the east coast, east of the Rocky Mountains, and in one western state, California. It loves human-inhabited areas, as our mowed lawns, open pastures, broad green meadows, and carefully maintained landscapes are prime habitats.

This mushroom species is spreading, too. The spores get spread with mulch (which happens with many mushrooms), and so it is being spread unintentionally through our landscapes.

False Parasol Identification

Season

The primary season for false parasols is late summer into fall, after heavy rains. However, it will appear from April through November in warmer climates like Florida or the Southwest.

Habitat

False parasols love open meadows, grassy lawns, front yards, mulched areas, and any place where there is plenty of sun and water and not a lot of shade. They often grow in substantial scattered groupings or fairy rings. This mushroom will also grow singularly or widely spaced. It is adaptive, a trait that allows it to spread much more widely than its original habitat.

These mushrooms appreciate human-disturbed and cleared lands, and you will find them almost always around human habitation.

Identification

When the false parasol is fully mature, it is easier to identify. It is when it is young that there is the most confusion.

The fruiting mushroom starts out as a small round white sphere on top of a slender whitish-brown stem. It looks rather like a golf ball atop a stem, with brown flecked decoration. As it matures, the cap opens up and flattens to look more like a dinner plate. Or a slightly down-curved dinner plate with a little bump at the top. The brown dots on top of the cap remain with maturity but might be brushed off from heavy rains or wind.

False parasol caps range in size from 4-11 inches wide. The top is a creamy white to pale tan. The scaly flecks on top are brownish to pinkish to light tan, and they cover the entirety of the cap. They’re a very noticeable feature.

As the mushroom matures and the cap flattens out, the scales may be more concentrated around the center and less apparent at the edges. The caps tend to get darker over time, sometimes turning wholly tan or brown.

Under the cap, the gills start out white, then mature to grayish green or brownish green. This is where it gets the common names, Green-Spored Parasol and Green Gill. This is an important identifying feature, as it is one of the few mushroom species with green gills. However, when they’re young and have white gills, they are almost indistinguishable from the Shaggy Parasol, Chlorophyllum rhacodes.

The stem of the false parasol is white to tan-brown and discolors brown a little bit when handled. It grows 3-8 inches long and is slender support for the large cap. The stem is slightly larger at the base and a little bit tapered at the top, where it attaches to the cap.

There is a whitish ring around the stem (a remnant from a partial veil when the mushroom was very young), about 1/3 down from the cap. The ring is thick and a greenish or brownish color only at the very lower edge where it meets the stem. The stem may have very fine fibrous growth, but not always; more often, it is bald and smooth.

The flesh of this mushroom is white and thick. The cap does not stain when cut, but the base of the stem might stain reddish or pinkish when cut.

The spore print is dull gray-green. Do a spore print of a mature mushroom – younger specimens may give off a white spore print simply because they aren’t fully developed yet. This mushroom does not have a distinctive smell.

False Parasol Lookalikes

Chlorophyllum brunneum

This relative to the vomiter is a great edible species from the west coast. It should only be foraged by those very clear on the differences, though, as they are pretty subtle. The primary identifier is habitat. The vomiter likes grasslands, meadows, and yards. C. brunneum prefers coastal areas around cypress and eucalyptus trees.

Chlorophyllum rhacodes (Shaggy Parasol)

A spore sprint is the best way to differentiate this edible species from the toxic false parasol. The shaggy parasol has a white spore print; the vomiter has a greenish spore print. On mature specimens, you can see the gill coloring without doing a spore print – but don’t forget that young false parasols often have whitish gills.

Both these species grow in meadows, are whitish with brownish scales, and have a ring around the stem. The mature gill coloring and spore print are the primary identifiers.

Macrolepiota procera (The Parasol Mushroom)

Like the false parasol, the true parasol grows in lawns, meadows, and open pastures. It is also often found growing in large groupings, including as a fairy ring. The parasol mushroom has white gills, sometimes with a pinkish tinge and a white spore print. When cut, the flesh usually turns pink but doesn’t always. The stem features a snakeskin-like pattern, with crackled brown fibrous material covering it entirely.

It looks pretty similar to the false parasol, and many times a spore print is necessary to determine what you have (remember, the vomiter has a greenish spore print).

In Europe, the false parasol is rare, so people forage the true parasol and shaggy parasol without worry. This is fine in Europe, but when the same foragers come to North America, they make the mistake of foraging the false parasol. Foragers from other parts of the world are among those most commonly poisoned by the vomiter due to mistaken identity with the true parasol.

Coprinus comatus (The Shaggy Mane)

The Shaggy mane, a good edible mushroom, looks slightly similar to the false parasol, but only when it is very young and just emerging. It is soon easy enough to tell them apart. Shaggy mane caps grow oblong, not golf-ball round like the false parasol. They also deteriorate very quickly into gross, inky messes. If you see a bunch of tall white mushrooms melting into black goo, it’s a shaggy mane.

Leucoagaricus americanus aka Lepiota bresadolae

This is another mushroom with a white cap, brown flecks and grows in landscaped human-disturbed areas. It prefers mulch as opposed to lawns but isn’t always so picky. This is an edible and foraged species.

The key to telling it apart from the false parasol is again in the gills. This mushroom has pinkish-brown gills. The flesh of L. americanus will also bruise when cut or squeezed, turning yellow at first, then staining to reddish-brown. False parasol flesh does not change color when cut.

Amanita thiersii

This amanita is not edible, so it should be left alone, too. From a distance, it looks quite similar to the false parasol, with the same white cap, white to light brown dots on the cap, and appearance in lawns and meadows. The main difference is that A.thiersii has white gills and is covered from cap to stem with shaggy and sticky white fibers from the universal veil.

False Parasol Common Questions

What do I do if I think I’ve accidentally consumed the false parasol (or my child or dog did)?

Call poison control immediately and listen to what they say. (800) 222-1222 (people) or (800) 426-4435 (animals)

Does the false parasol grow in cities and suburbs?

Yes! This mushroom seems to really like human-disturbed land, especially manicured lawns, baseball fields, schoolyards, and landscaped areas. You are more likely to encounter this mushroom in a suburban neighborhood than out in the woods hiking.

Luke says

(800) 426-4435 (animals) is not the correct #

It should say (888)426-4435

Jenny says

Oh shoot! Good catch, thank you, changing it now

Bob Kufert says

This should have been the first link to come up on a search for golf ball looking mushrooms. I was almost fooled into thinking these mushrooms that sprang up overnight on my lawn were puffballs. They are certainly innocent looking. Very glad I found this before sampling them.

Jenny says

We are very glad too!

Maria says

Great article. One thing I wish for in mushroom blogs is for them to show a side by side comparison of an edible mushroom next to the similar but toxic mushrooms, with the specific differentiating features side by side… so I don’t have to scroll down, and then back up, and down again…. Does that make sense?

Jenny says

Yes, totally makes sense. It takes a lot more work to do that, which is why it doesn’t often happen. But thank you for the reminder to do this more

tim carroll says

what are your thoughts on the macrolepiota macilenta? Looks almost identical to the false parasol but white spore print.

Jenny says

Yes, that is a newly described species which is basically identical to macrolepiota procera, which is described in this article.

John Flanery says

You say that the false parasol isn’t in the Pacific Northwest, but I just got a green spore print here in Eugene.

Jenny says

Thank you for pointing this out! That text should have said it is way less common in the Pacific Northwest. It does still appear there though. Fixing that now