If you’re out in the woods looking for oyster mushrooms, you might spot a small, tan mushroom that looks a lot like a baby oyster. Don’t get your hopes up, though—this is the bitter oyster mushroom, and it’s not a true oyster at all. Plus, it tastes pretty terrible. Still, the bitter oyster mushroom (Panellus stipticus) has its own claim to fame: it glows in the dark! Well, sometimes, anyway.

You have to be in the right part of the world to see the show. It seems like only the eastern North American specimens do this. In contrast, bitter oysters in the Pacific Northwest and Europe have no glow.

- Scientific Name: Panellus stipticus

- Common Names: Bitter oyster, Astringent panus, Luminescent panellus, or Stiptic fungus.

- Habitat: Dead and decaying hardwoods

- Edibility: Inedible

Jump to:

All About The Bitter Oyster Mushroom

French botanist Jean Bulliard first described this mushroom as Agaricus stypticus in 1783. The species underwent many and various classifications until 1879, when Finnish mycologist Petter Adolf Karsten gave it its current name, Panellus stipticus. This mushroom has been known by quite a few scientific names over time, including Agaricus flabelliformis, Panus stipticus, Pleurotus stipticus, and Lentinus stipticus.

The specific name “stipticus” (sometimes spelled “stypticus”) comes from its reported ability to constrict damaged blood vessels and stop bleeding—a styptic property. The name’s roots trace back to the Greek word “styptikós,” which means “to contract.”

Panellus stipticus by Jenn on Mushroom Observer

Bitter Oyster Mushroom Identification

Season

These mushrooms fruit from September through November. The timing does change by region, though – East and Central Texas specimens grow in late spring and early summer. These tough little mushrooms also often stick around all year. Unlike other mushrooms that decay and decompose in a few weeks, bitter oysters just dry out and stay on the log.

Habitat

Bitter oyster mushrooms grow on decaying hardwood trees. They’re often on fallen logs, big branches, and old stumps. North American bitter oysters love growing on oak, birch, maple, hickory, pecan, and American hornbeam. In East and Central Texas, these mushrooms tend to grow on live oak and post oak varieties more. While hardwoods are their favorite habitat, these adaptable fungi sometimes pop up on conifers such as loblolly pine and eastern white pine.

These mushrooms grow in thick, overlapping groups that can cover large parts of dead wood. These tight clusters – known as “imbricate shelves” – are like overlapping tiles or roof shingles. Bitter oyster mushrooms rarely grow alone. Instead, many mushrooms grow together in colonies that can spread across entire logs or branches. These mushrooms are most common in damp, shady spots where humidity helps the mycelium spread and fruit bodies develop.

The bitter oyster grows horizontally from its wooden host. If the log position is changed, the mushroom will reorient its growth to continue growing horizontally. This means you can find some wonky-shaped specimens in the wild.

Panellus stipticus by Aaron on Mushroom Observer

Identification

Cap

This mushroom is a slow grower. It starts out as tiny white knobs and then takes one to three months to develop caps. The bitter oyster mushroom has a kidney or clamshell-shaped cap. It is a small mushroom overall (much smaller than true oysters) with caps averaging 0.5 to 1.3 inches across. The cap starts rounded with the edges rolled under.

With age, the cap flattens out almost completely, so it is flat as a pancake. The top of the cap is finely wooly or velvety, though you may have to look super close to see it. Underneath the cap, the gills curve slightly inward along the edges, creating a scalloped pattern on the top of the cap.

In general, younger mushrooms are pale buff and then, with age, turn more cinnamon brown. However, the mushrooms can range in color from yellowish-orange to buff to cinnamon. The caps may also lighten with age.

Light exposure impacts the color of the cap a lot. When the mushrooms are in direct sunlight, the caps tend to be more cinnamon brown. When light is scarce or filtered, the caps will stay paler. Interestingly, if you add moisture to dried specimens, they revert to their original colors.

The cap surface often becomes wrinkled, somewhat cracked, and scaly with age. Cap surfaces often have a pattern of block-like areas similar to cracked dried mud when they’re older or past prime.

The caps sometimes have zonate patterns (these are lines of color alternating between light and dark bands). Zonation is influenced by fluctuations in environmental humidity. If there is a lot of moisture (humidity), the caps grow quickly, but when there is less moisture in the air, the caps slow down their growth.

This flucuation in growth happens throughout the lifetime of the individual caps and results in lines of color on the cap surface. This rapid or slowed growth doesn’t happen with all specimens and is entirely dependent on the environmental conditions where the mushroom is growing.

Gills

Gills on this mushroom are yellowish-brown to buff-colored and somewhat close together (the spacing varies a bit, but they usually aren’t super crowded). The gills branch out and connect through cross-veins, which creates a mesh-like pattern that is very unique. The gills stop abruptly at the stem; they do not run down it.

Stem

This mushroom has a short stem, 0.2 to 0.8 inches long, that looks like a stub. The stem base tapers where it meets the wood substrate. It is attached off-center to the cap. Like the cap, the stem is covered in fine, silky fibers that give it a fuzzy-velvety feel.

Taste and Smell

The mushroom does not have a distinct smell. It is known for its extremely bitter, acrid, or astringent taste that causes uncomfortable drying in the mouth. Be prepared if you taste test this one; you’ll want a big gulp of water (or something stronger).

Eastern North American specimens develop a gradually intensifying bitter taste that leaves the mouth dry.

Flesh and Staining

The flesh of this mushroom is thin, tough, and whitish to pale yellow-brownish. It does not change color or stain when cut or bruised. The leathery texture and bitter taste make it inedible.

Spore print

The bitter oyster produces white spore prints.

Panellus stipticus by purplecloud on Mushroom Observer

Panellus stipticus by Brian Hunt on Mushroom Observer

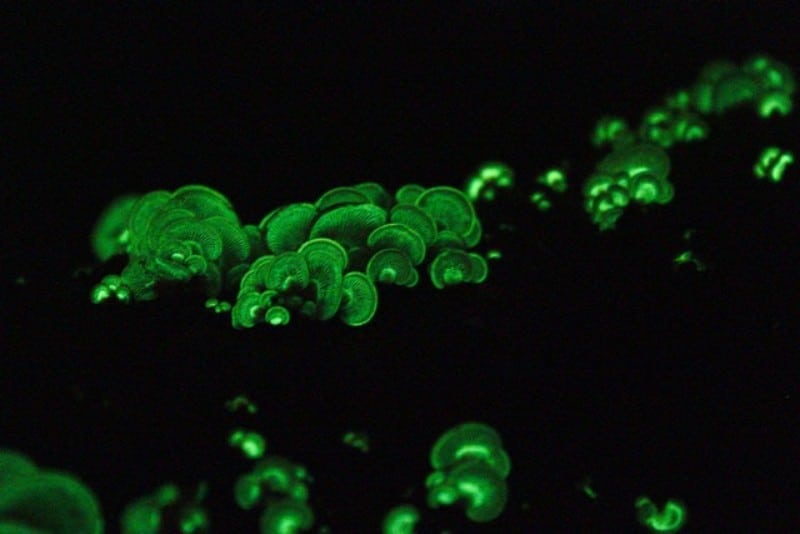

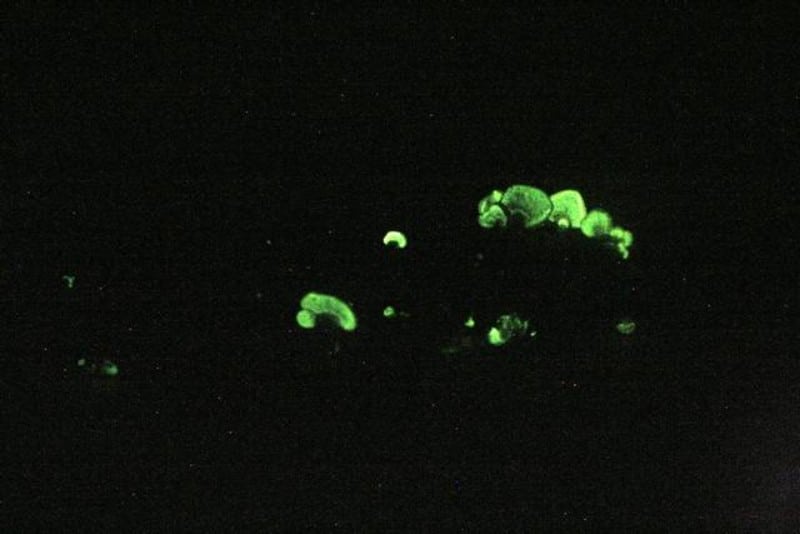

Bioluminescence: Why The Bitter Oyster Glows

The bitter oyster belongs to a special group of organisms that create their own light through chemical reactions. Unlike fireflies that flash on and off, these mushrooms give off a steady, soft glow under the right conditions. Among 70-80 species of light-emitting fungi, the bitter oyster mushroom is among the brightest.

The bitter oyster’s glow isn’t uniform across its body. The light concentrates along the gill edges, where gills connect to the stem and cap, and along the inrolled cap edge. And, the mycelium can also glow. The glow’s distribution matches the location of special cells called cheilocystidia. The mushroom will glow steadily in the right conditions and is thought to glow strongest when it is about to release its spores.

The bioluminescence is highly variable between fruit bodies found on different logs in different environments. It seems the environment may also play a key role in how bright the mushroom glows; it is far more than just an internal mechanism.

The fungus showed a clear daily pattern, with the brightest light observed between 6 and 9 pm. This was true whether the mycelial cultures were kept in constant light, constant darkness, or a regular day-night cycle.

Panellus stipticus mushrooms from Europe, western North America, Russia, Japan, and New Zealand usually can’t produce light. Only eastern North American bitter oyster mushrooms produce light. This is because a single dominant allele controls this luminescent trait, which is passed down through generations.

Research shows non-luminescent strains lack the complete gene cluster needed to make light. And, for some reason of Mother Nature and natural evolution, the eastern N. American species developed this trait and passed it on, while no others did.

The mushroom’s glow comes from a complex biochemical reaction. Compounds called luciferins interact with enzymes called luciferases when oxygen is present. This creates a green light. Oxygen plays a crucial role – without it, the mushroom stops glowing within an hour. The glow returns just eight minutes after oxygen becomes available again.

For a more detailed investigation into bioluminescence in mushrooms, check out our article Why Do Mushrooms Glow In The Dark?

How to see the glow

You’ll only see the glow at night or in a pitch-dark room. The darker, the better—any light pollution will ruin the effect. It’s easiest to find these mushrooms during the day, so either collect them then or mark the spot and come back after dark. They’ll still glow after you pick them, so no worries there. Even dried-out mushrooms can glow again if you soak them in water and let them air dry.

Bitter Oyster Mushroom Lookalikes

Oyster Mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus)

The true oyster mushroom is extremely similar looking, except it is much bigger, not hairy, and its gills are decurrent, meaning they run down the stem. They also usually smell distinctly like anise.

The bitter oyster mushroom’s gills do not run down the stem, the cap is finely velvety, and there is no distinct smell. These are significantly smaller than true oysters, which can get up to 5-8 inches wide.

Peeling Oysterling (Crepidotus mollis)

This species looks quite similar at first glance. It grows on dead wood and has a similar half-shell shape. They are also both quite small and pale tan to whitish to grayish. The most distinctive feature of the peeling oysterling, which is what gives it its common name, is a gelatinous cuticle that readily peels away from the cap.

The peeling oysterling also has soft, rubbery, and flabby flesh, while the bitter oyster has a dry, slightly hairy cap surface.

The two species can be reliably distinguished by their spore prints: Crepidotus mollis produces medium-brown spores, while Panellus stipticus produces white spores. Also, taste will definitely set them apart. The bitter taste of the bitter oyster is unmistakable; the peeling oyster has no distinctive taste.

Split gill mushroom (Schizophyllum commune)

These are both mushrooms that grow on wood and are half-shell shaped with whitish or grayish caps. The primary difference is the gills. The split gill has longitudinally split gill-folds on the underside, which gives the fungus its common name “split gill.” These unique gill structures appear as if they’ve been split down the middle, creating a series of folded plates rather than true gills.

The gills of the bitter oyster, in contrast, are closely-spaced and often forked with numerous interconnecting cross-veins. Taste is also a key determinant, as the bitter oyster lives up to its name and the split gill has a mild flavor.

Hairy Oyster (Panus neostrigosus or Lentinus strigosus)

The hairy oyster, also known as the Ruddy Panus, is significantly larger than the bitter oyster mushroom. Its caps reach up to 4 inches across compared to the bitter oyster’s 0.2 to 1.2 inches in diameter cap. This size difference is one of the most immediately noticeable distinctions between these two wood-decomposing fungi.

The color between these species also differs markedly. The hairy oyster is reddish to purplish-brown cap when young, often with distinctive violet tinges when fresh and moist, gradually fading to tan with age. In contrast, bitter oyster mushroom caps are tan to pale yellowish-brown or orangish-brown, sometimes fading to off-white. They completely lack the purple hues characteristic of the hairy oyster.

The gills also differ significantly. The hairy oyster has pale mauve or pale purple gills when young that gradually turn paler and eventually brown with age. Gills of the bitter oyster mushroom are pale golden to tan.

Late Fall Oyster (Sarcomyxa serotina)

The Late Fall Oyster is also a clam shell-shaped, shelf-like mushroom that grows on wood. The late fall oyster has much larger fruiting bodies, with caps ranging from 1 to 4.5 inches wide, while the bitter oyster is notably smaller, typically less than 1 inch in diameter. The Late Fall Oyster also is predominantly olive-green to brownish-green or occasionally with yellowish or violet tints, and has a distinctive slimy or sticky texture when wet.

The gills of these species are also markedly different. The late fall has light yellowish-orange gills that are close together, sometimes forking, and are adnate (attached to the stem with their entire width). The bitter oyster mushroom has thin, close gills that are typically cream to pale tan.

Oyster Rollrim (Tapinella panuoides)

Another half-shell shaped grayish/whitish/tannish species, the oyster rollrim looks quite a bit like the bitter oyster at first glance. However, the oyster rollrim is much larger with caps that can reach 2 to 4 inches in width. This size difference is one of the most immediately noticeable distinctions between these two species.

Oyster roll rims grow on conifers, also, not on hardwoods like the bitter oyster. And, the taste is quite different from the bitter oysters’ distinctive acrid taste. The oyster rollrim has no distinctive taste.

Tapinella panuoides by Cindy Trubovitz on Mushroom Observer

Bitter Oyster Mushroom Edibility

Technically, the bitter oyster isn’t poisonous, but you definitely won’t want to eat it. The taste is extremely bitter and astringent, and the mushroom is small and tough—basically, it’s the opposite of a good meal.

While the bitter intensity varies depending on where it grows, it’s always unpleasant. Scientists haven’t found any serious toxic effects, but there are reports of people throwing up after eating bitter oysters from certain areas. These symptoms likely come from the mushroom’s harsh astringent compounds rather than actual toxins.

Panellus stipticus by rocksalt on Mushroom Observer

Bitter Oyster Mushroom Traditional Uses and Medicinal Properties

The bitter oyster mushroom has been used in traditional Chinese medicine as a styptic treatment for centuries. They placed it right on the wounds to stop bleeding. The fungus’s power to squeeze damaged blood vessels creates this blood-clotting effect. Traditional healers knew that the same compounds that made the mushroom taste bitter also served a medical purpose.

Healers also used this mushroom as a “violent purgative”—basically, something to make you throw up. This probably comes from how the bitter taste hits people, which can vary by region. For example, mushrooms from Japan, New Zealand, and Russia often cause throat constriction and nausea, which explains why folks used them to clear out their systems.

On the science side, bitter oyster mushrooms have shown some pretty strong antioxidant activity and might even have antibacterial properties.

Bioremediation with Bitter Oyster Mushrooms

Researchers have also looked into using bitter oyster mushrooms for cleaning up pollution. They’re pretty good at breaking down toxic chemicals in the environment, like phenolic compounds and even some nasty pollutants from olive oil production and dioxins. Plus, because their glow fades when they’re exposed to things like heavy metals or pesticides, they can act as a natural biosensor for environmental toxins.

Common Questions About Bitter Oyster Mushrooms

Is the bitter oyster mushroom safe to eat?

While not toxic, the bitter oyster mushroom is considered inedible due to its intensely bitter taste and tough, leathery texture. It’s best to avoid consuming this mushroom as it may cause unpleasant effects like vomiting in some cases.

Do all bitter oyster mushrooms glow in the dark?

No, only bitter oyster mushrooms from eastern North America reliably produce bioluminescence. Specimens from Europe, western North America, and other continents typically lack this glowing ability.

When and where can I find bitter oyster mushrooms?

Bitter oyster mushrooms are typically found from autumn through early winter in North America and Europe. Look for them growing in clusters on decaying hardwood trees like oak, birch, and maple in moist, shaded forest environments.

What makes the bitter oyster mushroom glow?

The bioluminescence in bitter oyster mushrooms is caused by a chemical reaction involving compounds called luciferins and enzymes called luciferases in the presence of oxygen. This process produces a soft green light, primarily visible along the edges of the gills and cap.

Leave a Reply