Many people see mushrooms as simple organisms, but they are anything but that. The mushroom lifecycle is complex, fascinating, and something every forager and enthusiast should understand. Part of finding and foraging mushrooms is also learning their growth process, so you know when to look and what to look for, and at what stage a mushroom is in when you find it. Understanding the mushroom lifecycle also helps a person make good foraging choices. Our actions directly impact the mushrooms and the environment.

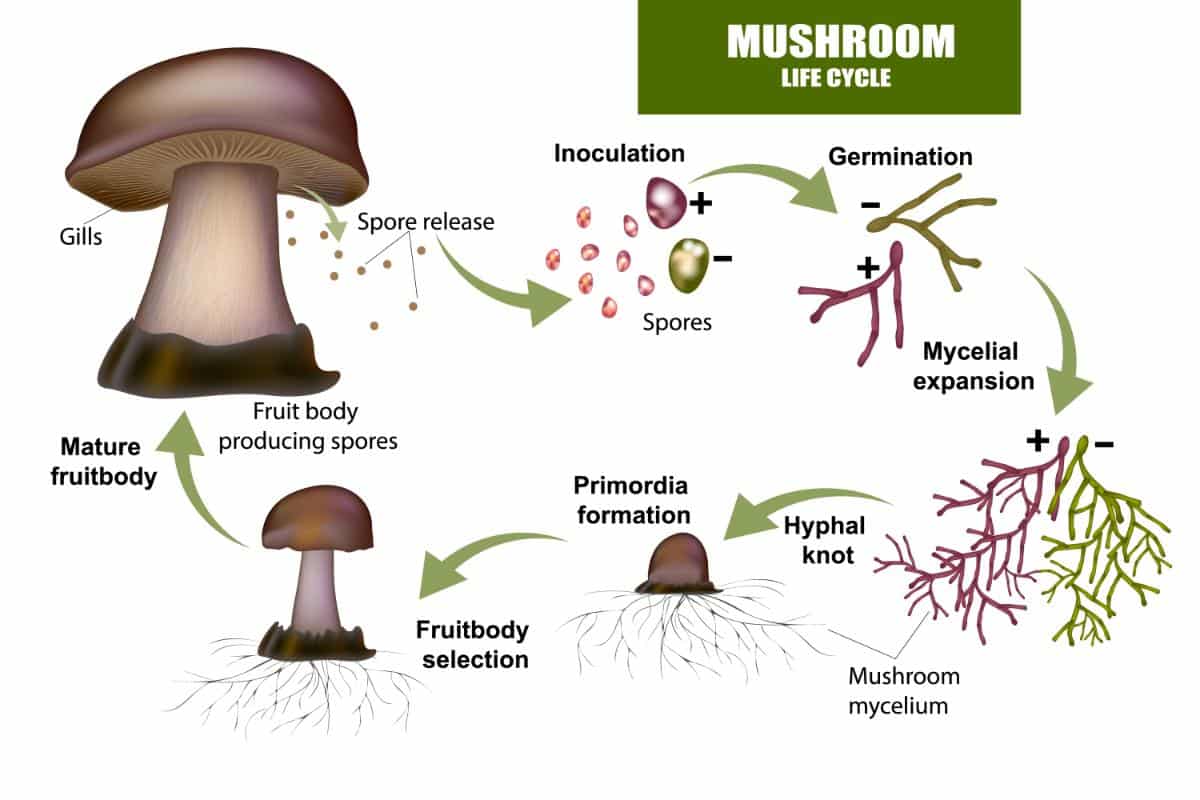

A mushroom’s lifecycle has four stages: spore germination, colonization, fruiting, and sporulation. There are roughly 20,000 mushroom-forming species worldwide. These are mushrooms that we can physically see because they produce a fruiting body. Yet this is just a fraction of the estimated 140,000 fungi species that exist. There are thousands of mushrooms that do not produce noticeable fruiting bodies or do so only rarely.

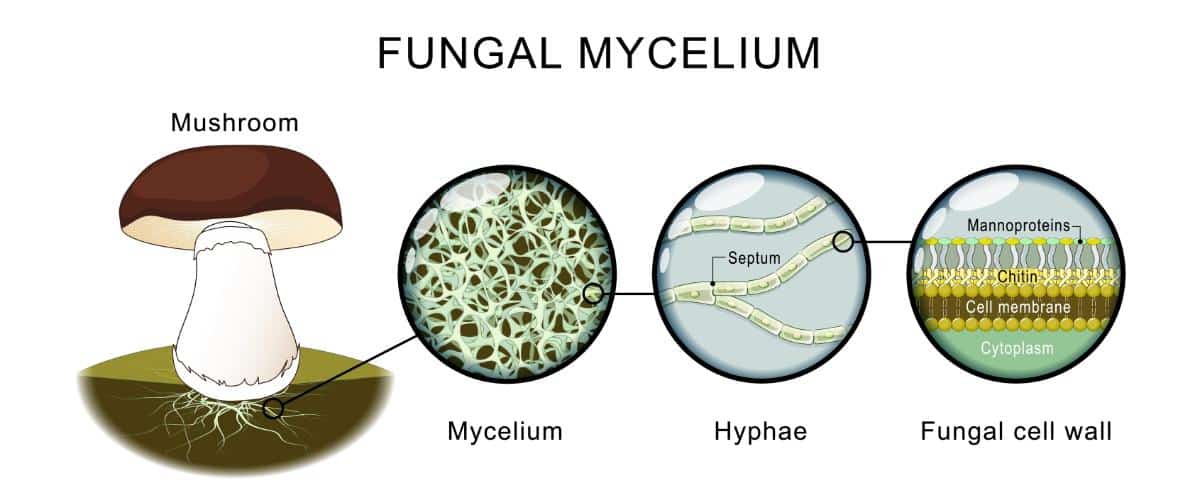

Scientists classify an organism as a fungus based on three points.

- Their cell walls contain chitin.

- They digest food through absorption.

- They cannot produce their own food (making them heterotrophic).

Jump to:

Fungi Compared to Plants and Animals

People mistakenly thought fungi were plants for hundreds of years because they don’t move and have cell walls. It’s an easy mistake to make when you’re trying to divide the natural world into easy groupings, and some groups outwardly follow similar patterns of growth. But molecular evidence actually shows fungi are more like animals than plants. This connection is seen in the fungi’s protein sequences that look a lot like animal proteins.

One primary difference between plants and fungi is how they get nutrients to survive. Plants create their food through photosynthesis. Fungi do not use photosynthesis. They need to get carbon from other sources, just like animals do.

However, even though animals and fungi are similar in that they need carbon, they find and consume it differently. Animals (like humans) eat the food first and then digest the nutrients inside their bodies. Fungi, on the other hand, digest their food outside their bodies and then absorb it.

The cells of plants, animals, and fungi are built differently, too. Both plants and fungi have cell walls. However, fungi’s cell walls contain chitin while plants contain cellulose. Chitin creates rigid walls, which give fungi their strength and let them keep their shape without any skeleton inside or outside their bodies.

Chitin builds microfibrils (fine, fiber-like strands) in fungal cell walls that are stronger than bone or steel by weight. These chitin microfibrils work together to create a three-dimensional network that makes fungi incredibly sturdy.

Fungi get their food in three main ways. They either break down dead organic matter as saprotrophs, feed on living hosts as parasites, or form beneficial partnerships with other organisms. Or, some combination of the three. This flexible approach to nutrition makes fungi key players in recycling nutrients and keeping ecosystems healthy worldwide.

The Mushroom Life Cycle Step-by-Step

Stage 1: Spore germination

The mushroom lifecycle starts when a microscopic spore lands on the right substrate. Substrate is a growing material, like woody debris, mulch, specific tree species, animal dung, and soil. The mushroom spores are single cells with no internal food reserves, so they sit there and wait for the right time and resources to be available.

Many fungi can reproduce both sexually and asexually, which makes them exceptionally adaptable. They don’t necessarily need a “male” and “female.” In fact, these terms don’t really apply to how fungi reproduce. Some are homothallic, meaning they can mate with themselves. Others are heterothallic species where only isolates of opposite mating types can mate.

The dormant spore wakes up when conditions provide adequate moisture and good temperatures. Temperature needs vary by species; some like chillier weather, while others prefer a more ambient climate. But they all need water. Although water needs also vary greatly among species, some fungi need tons of water to start their lifecycle, while others have adapted to needing very little.

The spore, once it awakens from dormancy, releases digestive enzymes that break down nearby organic matter into simple compounds it can absorb. Now, it is eating and getting nutrients so it can grow.

A small strand of mycelium called a germ tube then grows from the spore. This first growth helps the fungus establish itself in its new home.

Stage 2: Hyphae and mycelium growth

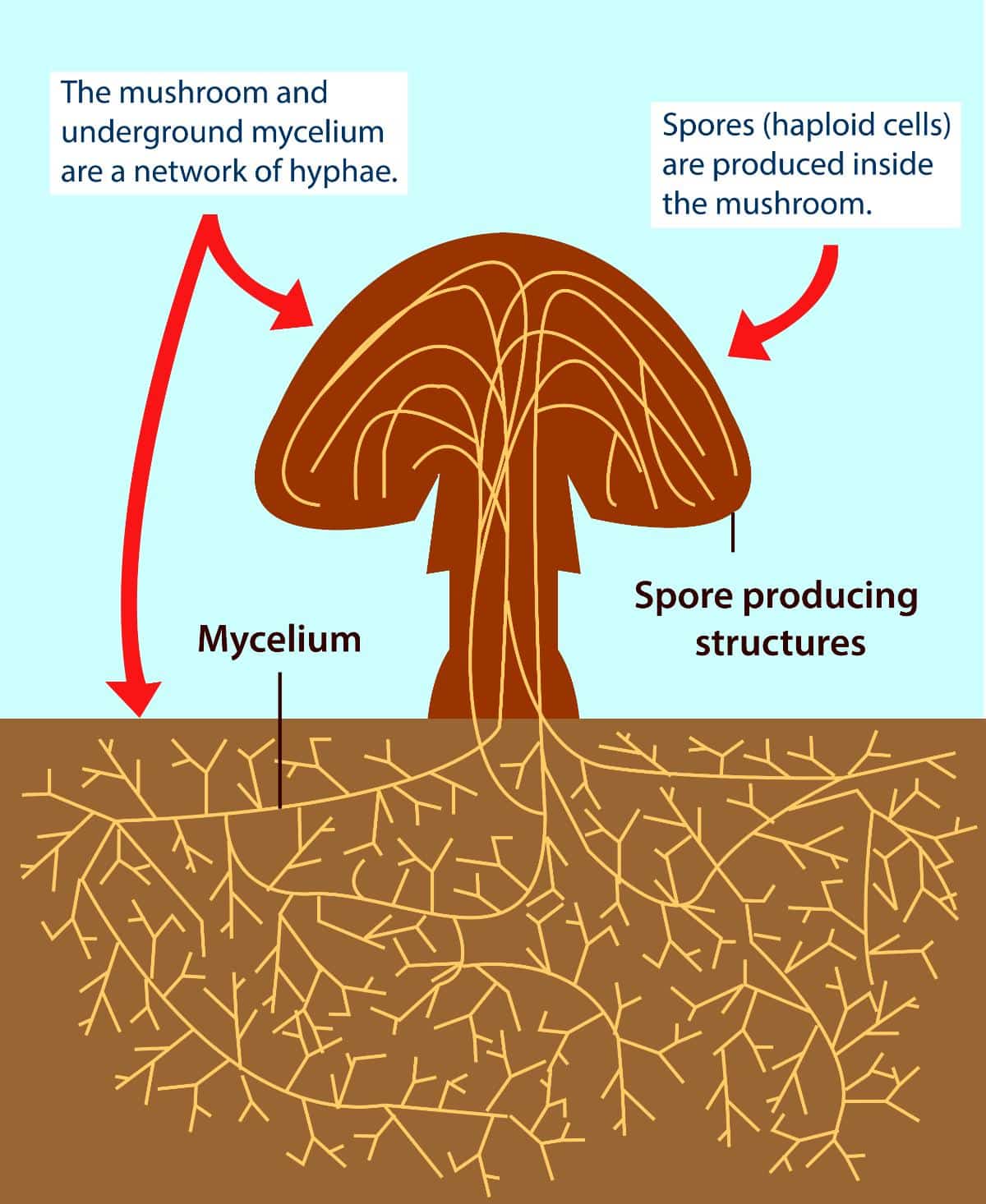

That little germ tube grows into hyphae. Hyphae are thread-like structures that are the foundations of fungal growth. They are tiny and thin, and hard to see on their own. As they grow and spread and join together into an intricate web, they become mycelium. Mycelium is simply thousands of hyphae interwoven into a single mass.

The hyphae spread through the substrate by growing at their tips. The tips work as collection points for vesicles that form inside the hyphal network. Vesicles are small sacs made of a membrane that work like delivery trucks, carrying molecules such as proteins, lipids, and RNA to keep the cell wall healthy, protect the cell, provide nutrition, and help with communication.

The hyphae network gets bigger and bigger, and as a collective mass, it is called mycelium. Mycelium is much like the root structure of trees or plants. It keeps the fungi grounded and establishes a stable base for the mushroom to eventually grow from. It also works on securing nutrients and maintaining the health of the mycelium network.

The mycelium releases enzymes during this colonization, spreading out and establishing its place. These enzymes break down complex organic materials into simpler compounds and transport them throughout the mass.

Stage 3: Fruiting body formation

When conditions are proper (for the specific species), the mycelium is triggered to form fruiting bodies. These triggers usually come from changes in humidity, temperature, or light exposure. Every species has its own triggers; not all mushrooms respond to the same environmental cues.

Many times, if the environment is not providing the necessary optimal conditions, the mycelium mass will not produce a fruiting body at all. It will wait another year, or longer (fungi can be very patient), until the conditions are exactly right, then it will fruit. Some species aren’t as picky – they are more laid-back about the environmental triggers or have a wider range of temperature and weather requirements.

The individual hyphae first bundle together to create hyphal knots. These dense, knotted clusters grow into small, visible bumps called primordia or “pins.” The pins expand into the mushrooms with stems, caps, and spore-producing structures (gills, pores, or teeth) underneath.

Stage 4: Spore release and dispersal

The mushroom’s life cycle peaks when mature fruiting bodies release their spores. The spores are released from the spore surface, either the gills, teeth, or pores. Then the cycle begins again.

Environmental Factors That Influence Mushroom Growth

Temperature and Humidity

Most mushroom species grow in temperatures between 65-75°F (18-23°C), though each species has its own needs and requirements. Humidity is also a vital factor. Many mushrooms need relative humidity levels between 85-95% in order to fruit. The high moisture level matters because mushroom bodies are 70-90% water. And, this water comes from their growing environment.

Substrate (Growing Material)

The substrate is the material that the mushroom is growing on. This might be trees, dead wood, mulch, soil, leaf litter, and even pinecones and acorns. Substrates give mushrooms both shelter and nourishment. Each mushroom species has its own substrate preferences, and many are hyper-specific to the type.

Oyster mushrooms, for example, only grow on certain types of trees. You won’t find them just anywhere. Morels grow on the ground; you won’t find them growing on trees or wood. However, they grow in association with specific trees, in a mycorrhizal relationship, and so you’ll only have success finding them if you look around those trees. If these trees are removed from the environment, the morels won’t grow.

Light and Air

Most mushrooms need some exposure to light to develop normal fruiting bodies. Fresh air is also a vital part of the growth process because, as fungi release carbon dioxide, they take in oxygen. Poor airflow results in weirdly long stems and small caps in many species.

Why the Mushroom Lifecycle Matters

Fungi are one of Mother Nature’s main recyclers. They break down dead organisms and return vital nutrients to the soil. Their decomposition activities turn potential piles of dead plants and animals into fertile soil that feeds new growth. Plants and fungi also create remarkable partnerships – approximately 80% to 90% of plant species enter into some type of symbiotic relationship with fungi. The fungi help plants get water and phosphorus. They also boost plant resistance against soil-borne pathogens.

Common Questions About Mushroom Growth and the Mushroom Lifecycle

Can a mushroom regrow from where it was cut?

Wild mushrooms don’t grow back from cut stems. New growth may appear, but it won’t be from the same place that was cut. For example, if you slice off a piece of chicken of the woods, growth will stop in that spot. But cutting off that one piece doesn’t hurt or stop the mushroom from growing in other areas. New growth may appear and spread around the cut area, but it won’t regrow from the cut.

The same is true with mushrooms like morels and chanterelles. When you cut the base of the stem to harvest the mushroom, a new one will not regrow from that stem. More may grow in the same areas and close by, but once that singular stem is cut, that’s it for that specific fruiting body.

Does cutting the fruiting body kill the mushroom?

Not at all. The fruiting body (mushroom) is just a temporary reproductive structure of the fungus, like an apple on an apple tree. The fungus’s main body—the mycelium—stays alive underground or within substrate throughout the year. Studies show that cutting or pulling mushrooms doesn’t affect the fungus’s future fruiting ability by a lot.

The mycelium keeps producing mushrooms during the fruiting season, whatever harvest method you use. The largest longitudinal study in Switzerland (1975-2003) shows that harvesting mushrooms doesn’t harm future harvests. Too much foot traffic, though, can reduce fruiting body production by about 30%.

Do mushrooms grow in the same place year after year?

Yes, it is common for many mushroom species to form lasting mycelia that produce mushrooms repeatedly in the same spot. If you discover a good edible species, even if it is past its prime in the moment, mark the spot for the following year! Whether they reappear will depend on good environmental conditions and access to nutrients, so it may vary some years, too.

How long does it take for mushrooms to grow from spores?

The time it takes for mushrooms to grow from spores varies widely depending on the species and environmental conditions. Generally, it can take anywhere from a few weeks to several months for the complete mushroom lifecycle from spore germination to fruiting body formation.

Do mushrooms need light to grow?

Contrary to popular belief, many mushrooms do require some light exposure to develop normal fruiting bodies. However, the amount of light needed is generally less than what plants require for photosynthesis.

How can I tell if a mushroom is safe to forage at each lifecycle stage?

Identifying mushrooms requires understanding their complete lifecycle changes. Young mushrooms might have stronger colors that will fade or wash out with age, rain, or sun exposure. As mushrooms mature, their caps expand and can look markedly different from young specimens. The gills or pores often become more pronounced, and veils that once covered the pore surface will rupture to form rings on stems. The mushroom lifecycle is heavily influenced by the environment and most mushrooms go through several stages of growth.

Never rely on “rules of thumb” like color or size for safety; instead, learn one distinctive species at a time and ensure 100% positive identification using multiple methods, including spore prints, expert verification, and comprehensive field guides specific to your region. Remember that young mushrooms can be just as toxic as mature ones, and if you have even 1% doubt about identification at any growth stage, follow the “when in doubt, throw it out” rule.

When is the best time of year or conditions to look for edible mushrooms?

It depends on the species. In general, the most fruitful time for mushroom foraging is in the fall, but mushrooms grow in spring, summer, fall, and winter.

Are there sustainable harvesting practices I should follow to protect mushroom populations?

It’s best to always forage with the forest in mind. It doesn’t hurt the mushrooms to remove them all – the mycelium is underground or in the substrate and protected. However, other creatures in the forest may rely on mushrooms as a food source, and taking them all could impact their life cycles.

Also, harvesting every single mushroom before it can spread its spores means that you are preventing the mushroom from reproducing. Foraging often interrupts the mushroom lifecycle Again, the current patch is fine, it’s established and will continue to do its thing. However, without spores being spread, new patches won’t form, and that will likely negatively affect the forest as a whole.

Leave a Reply