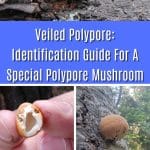

The veiled polypore (Cryptoporus volvatus) looks like a white or tan hard bubble popping out of a conifer tree. It resembles a little puffball, except it’s hard and often shiny. It’s hard to tell it’s even a fungus at all, at first glance. This species causes lots of confusion, even among experienced foragers.

Even though the veiled polypore is small, it is very attention-getting because it is so weird. The often shiny blobs really stand out against the dark bark of conifer trees, and they often appear in large numbers. And, they have a hard exterior and a hollow interior, which is equally as unusual. It is unlike any other polypore in North America in the way it forms and grows.

The veiled polypore has shown promise in lab studies and may be useful in treating tumors and H1N1 swine flu. It is not an edible mushroom, though, due to its texture and very bitter taste. North America has just one species of Cryptoporus, but there are other species in other countries.

- Scientific Name: Cryptoporus volvatus

- Common Names: Veiled Polypore

- Habitat: Dead conifer trees

- Edibility: Inedible

Jump to:

All About The Veiled Polypore

American mycologist Charles Horton Peck first described the veiled polypore to science as Polyporus volvatus in 1875. The mushroom has many synonyms, including Fomes volvatus, Polyporus obvolutus, and Scindalma volvatum.

The name Cryptoporus is derived from the Greek “kryptos,” meaning “hidden,” and the Latin “porus,” meaning “an opening.” It was given this name because of the veil-like membrane that covers its pores and the small hole that opens at the base to release the spores. It is a veiled mushroom with a hidden opening.

There are only two species in the Cryptoporus genus. This species, which is somewhat widespread, and a species in southern China, Cryptoporus sinensis. These two species look identical but C. sinensis produces smaller spores.

Veiled Polypore Identification Guide

Season

Fresh fruiting bodies typically show up from summer through fall. Warmer areas might see them stay around through winter.

Habitat

The veiled polypore grows on coniferous trees, particularly on pines (Pinus species). It does grow on other conifers, though, like balsam fir, hemlock, and tamarack. Veiled polypores usually appear on trees that have died recently, usually within two years after death. It is uncommon to see them on trees that have been dead for over two years.

Many fungi prefer well-rotted wood, but the veiled polypore is more strategic and is one of the first organisms to show up. The fungus creates a brown rot that targets the sapwood. This leads to decay just beneath the bark.

Veiled polypores also take advantage of trees that’ve suffered calamities. One common situation they take advantage of is pine beetle infestations. Pine beetles create openings in the tree bark and weaken the tree’s natural defenses. The veiled polypore loves this and might grow right out of beetle holes after pine beetles have attacked a tree. These trees develop what researchers call a “mycological rash”. This pattern is so consistent that many veiled polypore fruiting bodies on a tree point to beetle infestation. Trees that have been weakened by fire also become easy targets.

The veiled polypore is widespread across North America, but it appears less frequently in central states, the Great Plains, and southeastern areas. It is also found in South America, Japan, and China.

Identification

Cap

The cap of the veiled polypore ½-3¼ inches across and ½-1 inch thick. The young mushrooms are small, white or tan, and spherical in shape. With maturity, they gradually change to rounded, semicircular, or hoof-shaped. The young mushrooms are cream to yellowish or pale tan, and sometimes have a glossy appearance. It looks like someone buffed them or covered them in lacquer. This gloss is a layer of sap from the host tree. The cap’s surface is smooth without decorations. It loses its vibrancy and turns more buff-brown as it ages. Mushrooms that are past maturity are often bleached white, cracked, and crumbly.

Stem

The veiled polypore has no stem. The fruiting body grows directly out of the wood, creating its shelf-like or hoof-like shape as it extends from the tree.

Pores

The fungus’s most unique feature is the way the pores are protected. The cap edge grows downward, curved under to form a tough, whitish to buff-brown membrane or veil. This membrane completely covers the pore surface and protects it from the elements.

Spore print

The spore print is pinkish to pinkish-buff in color.

The Unique Spore Dispersal Strategy of the Veiled Polypore

The majority of polypores, and mushrooms in general, release their spores (their “seeds”) from under their caps at maturity. The spores are then carried by the wind, rain, insects, and animals to spread in the forest and hopefully, create new colonies. These fungi all primarily rely on wind to disperse their spores. Because of this, it is essential for these mushrooms to have their spore surface (pores or gills) exposed to the elements so that this can occur.

Some mushrooms develop veils under their bores or gills to protect the spores while the mushroom is young. Then, as the mushroom grows, the veil breaks to reveal the spore surface and allow them to be spread. This is widespread among gilled mushrooms and boletes, but is very uncommon with polypore mushrooms.

The veiled polypore, though, is a polypore with a veil. The fungus’s distinctive veil creates an enclosed chamber under the pore surface that collects billions of spores. When the mushroom matures, instead of having its spore surface open to the wind or rain, it is covered and protected, and all the spores accumulate in one place. This might seem strange at first – why would any fungus want to trap its own reproductive material?

Scientists believe that this specialized veil helps retain moisture within the fungus and protects the spore surface from drying out. This keeps the spores alive as they fall from the pore surface. Such an adaptation is especially valuable since the veiled polypore often fruits in areas with limited rainfall.

There are several theories regarding how the veiled polypore distributes its spores and the purpose of the protective veil that covers the spores. In reality, it is likely a combination of all three theories, rather than just one over the other. Mushrooms often have several methods to spread their spores and improve reproduction chances.

Theory 1: Insect Dispersal

To spread its spores effectively, the veiled polypore has evolved a unique dispersal method. It develops a small opening (ostiole) at its base as it matures. Insects like to eat the spores, and so they go through the opening for a quick meal. As the insects eat, the spores end up covering their entire bodies. When they leave the mushroom, they take all those spores with them and unwittingly spread them all over the forest.

A Japanese research team tracked the number of insects that visit these mushrooms, and it is pretty incredible. They found 8,990 insects from 17 different insect species in 438 veiled polypore mushrooms. This means each fungus hosted more than 20 insects. These tiny visitors end up covered in tens of thousands of spores that they might carry to new trees.

In Korea, a similar study was done, with similar results. Their collection of 70 different veiled polypore mushrooms found 251 individual insects (6 different species) across them. This averages out to 3.5 insects per mushroom.

Theory 2: Passive Dispersal

Researchers at Iowa State University have challenged the theory of insect dispersal. Their work revealed that 2.5 billion spores escaped through the veil’s opening without any help from insects. They suggest that the veil helps the fungus survive dry conditions by protecting the spore surface.

This adaptation enables the fungus to produce spores during periods of low rainfall and humidity, conditions in which these mushrooms are often found. Then, when the time is right, the spores push out the hole in the base without assistance. The passive dispersal theory suggests that air currents may be the main way this fungus spreads its spores, just like other polypores.

Theory 3: Woodpecker Dispersal

White-headed woodpeckers often search for wood-boring beetles in and around these mushrooms. They’ve learned that the beetles can be found in the mushrooms. The woodpeckers break open the veiled polypores to get at the beetles inside. The birds then get the spores on their bodies and become accidental spore spreaders when they tear open the fruiting bodies to reach the insects.

Veiled Polypore Lookalikes

Red-Belted Conk (Fomitopsis pinicola)

The red-belted conk may be confused with the veiled polypore when it is very young. When it is just emerging, the red-belted conk is a small, whitish, hard growth that emerges from a tree. It is also found in conifer forests, like the veiled polypore. Once the red-belted polypore starts growing, however, it is easy to differentiate them.

The veiled polypore stays small, rarely getting more than 3″ wide, while the red belted polypore gets quite large – up to 30″ wide! It also grows in a wide, bracket-like shape and develops reddish-brown coloring with age.

Artist’s Conk (Ganoderma applanatum)

Like with the red-belted conk, the artist’s conk looks similar to the veiled polypore only when it is very young. Young artist conks growths are also small, whitish blobs growing on the tree. As soon as it starts getting big, it is obvious that it is not the veiled polypore. The Artist’s Conk has a large exposed white pore surface that bruises brown when scratched (a distinctive feature used by artists.

Birch Polypore (Fomitopsis betulinus)

Very young birch polypore mushrooms are whitish to tan, small, and emerge out of wood just like the veiled polypore. However, they get much, much bigger, and even when they’re young are generally bigger than the veiled polypore. These mushrooms also grow primarily on birch trees, not on conifers.

Veiled Polypore Edibility

The veiled polypore is inedible. It has a tough, woody texture and a very bitter taste. The fruiting body becomes corky and stays that way even after cooking, which makes it unpleasant to eat.

Medicinal Uses For The Veiled Polypore

The Asian veiled polypore variant has been part of traditional Chinese medicine since the 15th century. It is mainly used to treat asthma and bronchitis. Recent research has shown that aqueous extracts from Cryptoporus volvatus effectively combat the influenza A virus in laboratory and living organisms.

Scientists have identified several bioactive compounds, including β-glucans, triterpenes, and cryptoporic acids, that help reduce inflammation and modulate immune responses. These discoveries suggest potential treatments for airway inflammation, which may explain why people have used it for respiratory issues for centuries.

Common Questions About The Veiled Polypore

What makes the veiled polypore different from other polypore mushrooms?

The veiled polypore is distinctive because of its rounded, puffball-like shape and hard, dense texture. It also has a membrane that completely hides its pores from view. It’s the only polypore species with this unique veil-like structure.

Where can I find the veiled polypore in nature?

You can find the veiled polypore on recently dead coniferous trees, especially pines. It’s commonly seen after beetle infestations or forest fires, and is widespread in North America, South America, and Eastern Asia.

Is the veiled polypore edible?

No, the veiled polypore is not edible due to its extremely tough and woody texture. It’s primarily valued for its ecological role and potential medicinal properties rather than as a food source.

What is the purpose of the veil on the veiled polypore?

The veil likely serves multiple purposes. It may help retain moisture, protecting the spores from drying out. It also creates a chamber where spores can accumulate in a protective environment. Then, when the mushrooms are mature, a small hole opens up at the base to disperse spores through insects or air currents.

Leave a Reply