Verpa mushrooms cause a lot of confusion during morel season. These mushrooms are closely related to morels and appear at the same time of year (spring). They are also called or grouped with the mushrooms known as “false morels.” This terminology isn’t exactly fair to Verpa mushrooms. Even though they aren’t true morels, they aren’t toxic or problematic. In fact, they’re an edible species that shouldn’t be overlooked.

There are several lookalikes, though, so, as with morels, forage these mushrooms carefully and be very sure you’ve properly identified them. There are two primary species of Verpa mushrooms in North America, and they grow across North America.

- Scientific Name: Verpa bohemica, Verpa conica

- Common Names: Early morels, thimble mushroom, thimble fungus, wrinkled thimble cap, thimble caps, early false morel

- Habitat: On the ground, particularly in wet areas

- Edibility: Edible

Jump to:

All About Verpa Mushrooms

These mushrooms, also known as “early morels” or “wrinkled thimble-caps,” are very misunderstood. They belong to the same Morchellaceae family as true morels, but a 1970s publication erroneously made unproven claims about toxins. This, as you can imagine, led to a decades-long (and still ongoing) fear of Verpa mushrooms.

The nickname “early morel” comes from the time they appear – before morels in the spring. The names “thimble caps” or “thimble fungus” refer to how their cap hangs freely around the stem, just like a thimble on a finger.

Both Verpa species also have their own individual common names. Verpa bohemica is known as the “wrinkled thimble-cap” and sometimes “early false morel.” Verpa conica is also called the “bell morel” or “smooth thimble cap.” The Germans call it “Fingerhutverpel,” which is a direct reference to its thimble-like shape.

The second name, “bohemica,” refers to the species being first documented in Bohemia (now part of the Czech Republic). “Conica” describes the distinctive cone-shaped cap of the species.

Verpa mushrooms sit between cup fungi and true morels in both looks and development. There are five recognized species worldwide, with two appearing in North America: Verpa bohemica and Verpa conica.

Verpa mushrooms share a close relationship with true morels, but they remain distinct despite their similar appearance. The main difference lies in how their caps attach. Verpa caps only connect at the top of the stem, while true morels (except Morchella semilibera) have caps that fully join with the stem.

The Verpa taxonomy has undergone several changes, and the species has bounced between various genera, including Leotia, Relhanum, and Monka, before settling in Verpa. DNA analysis firmly places Verpa within the Morchellaceae family, alongside Morchella (true morels) and Disciotis (cup-shaped fungi). These mushrooms have close evolutionary ties.

Verpas bridge the gap between cup fungi and true morels. Cup fungi likely started by growing a stalk to lift themselves above ground. V. conica’s thimble-like structure came next, followed by V. bohemica’s wrinkled surface that creates more space for spores. The true morel form emerged when the cap finally fused with the stem.

Verpa Mushroom Misconceptions: Setting The Record Straight

The story of Verpa edibility is an unfortunate one, shaped by misconceptions about its toxicity. In general, you’ll see these mushrooms listed as toxic or simply inedible. This is especially true in older guidebooks. This has led to a very confusing edibility status that continues to this day, despite evidence to the contrary. The primary reason is that the warnings have been passed through generations of foragers and are now repeated as fact.

North America’s hesitation toward Verpas started with Lincoff and Mitchel’s 1977 toxicology book. They suggested—without proof—that Verpa bohemica might contain gyromitrin. This unproven idea spread and eventually led the FDA to label them as toxic. This was unfortunate for the species and also somewhat surprising since Lincoff was an extremely well-respected mycologist, as was Sam Mitchel. It is likely they were simply erring on the side of caution because they weren’t sure, but it led to a very long avoidance of this edible species. Their status and renown also led people to take their words with an extra grain of salt, and this is how the Verpa misconception took such hold.

The truth is that lab tests show no gyromitrin or coprine toxins. Verpa mushrooms are completely safe to eat, or as safe as morels, which can be toxic if not cooked properly. This toxicity does not affect the thousands of people who forage morels every year with gusto. Just remember to always (ALWAYS) cook your mushrooms thoroughly.

More modern mycology books and mushroom foraging guides list Verpa conica and Verpa bohemica correctly as “edible” with no cautionary notes. Verpa species aren’t any more toxic than the true morel, and they should be treated the same. Research suggests that the symptoms people report after eating verpas might match the “cerebellar syndrome” sometimes linked to true morels.

The spread of wrong information about early morels has created an unexpected benefit for informed foragers. Once you know the truth about these wild delicacies, you can use them to your advantage. While other people are avoiding them, you can forage them with abandon and have some very excellent wild mushroom meals!

Verpas Around The World

The world sees the Verpa species quite differently outside North America. These mushrooms are widely foraged and eaten in other parts of the world. They are even sold commercially. In Europe, and especially in Northern Italy, Verpa mushrooms are part of the culture where they’re regularly collected and eaten. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) lists Verpa bohemica among its global wild food fungi and ranks them as “economically important wild fungi.”

The French celebrate Verpa bohemica as a “champignon de printemp” (spring mushroom). In North America, though, the FDA blocks dried and canned morels with Verpas from entering the US.

North American Verpa Identification

There are two distinct Verpa species in North American forests. They are very similar but have distinct differences that set them apart from each other. This guide covers the primary features that identify a mushroom as a Verpa, and the differences between the two species.

Season

Early spring, usually showing up before the true morels. In most regions, they appear shortly after the leaves begin to form on deciduous trees.

Habitat

Verpa mushrooms grow on the ground, usually in decaying leaf litter and wood debris. They never grow on wood or trees, though. Verpa habitat often includes cottonwoods, willows, and aspens. They also grow with other hardwood trees and sometimes with conifers. It is thought they are mycorrhizal, or at least so for part of their lifecycle.

The mushrooms grow singly, usually in dense or scattered groupings. They rarely, if ever, grow in clusters or clumps.

The best places to look for them are in bottomlands, river valleys, and wet woodlands. Sandy soil near riverbeds is often a prime habitat. They commonly grow near water, and you’ll often find them growing around the edges of boggy areas with standing water or ponds. They also tend to commonly fruit along shaded trails and at forest clearing edges.

Verpa bohemica grows across northern North America and throughout Europe, fruiting in Austria, the Czech Republic, Finland, Germany, Norway, Poland, Russia, Spain, and Sweden. It generally doesn’t appear south of Virginia. It grows up the northern California coast and in the PNW, but is seemingly completely absent in the middle of the country.

Verpa conica is a more widespread species in North America. It fruits in the northeast, though also generally no further south than Virginia. This species’ range extends from the northeast to Missouri, but is then absent from the southwest and from most of the northwest, except California and the PNW.

Identification

Cap

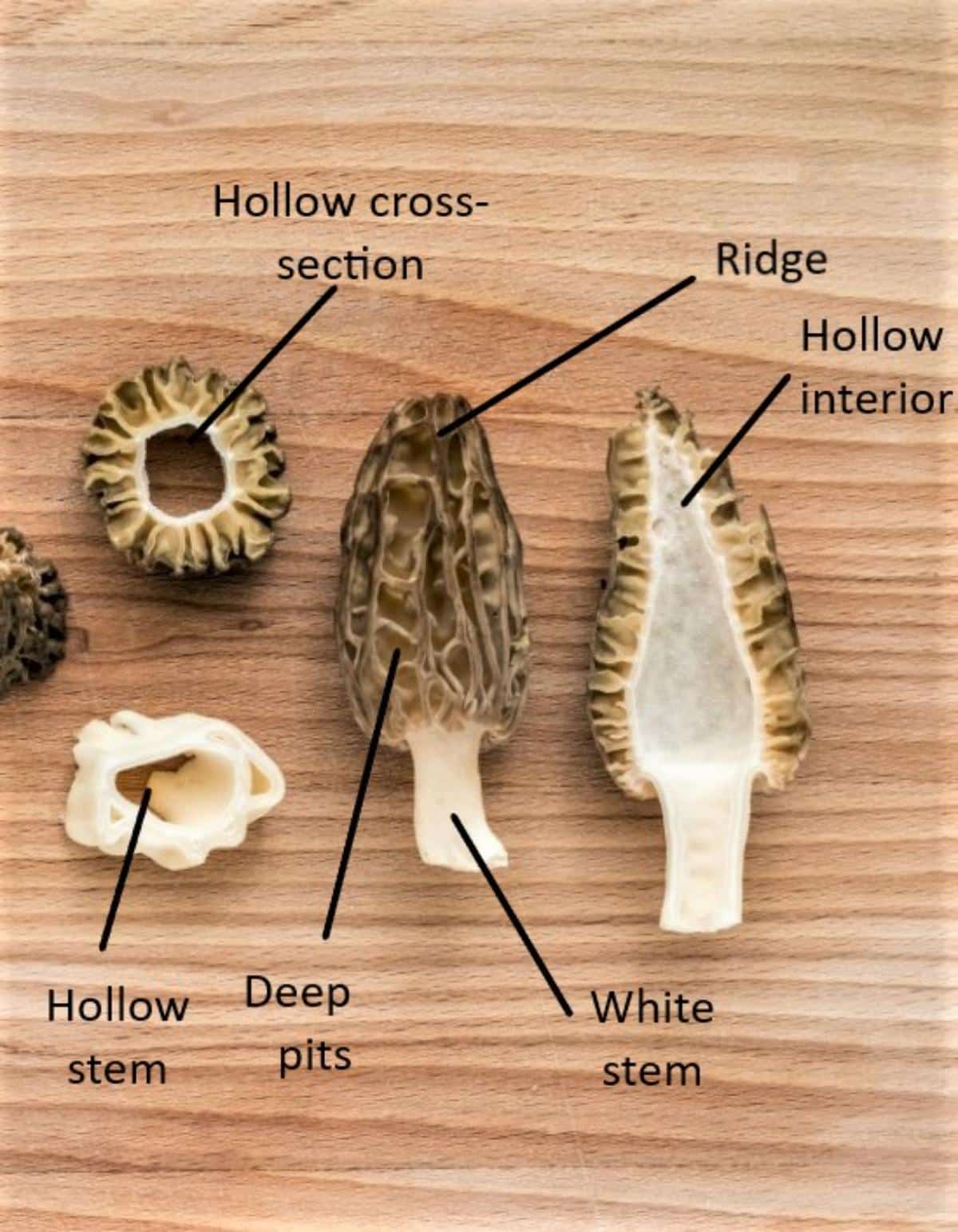

The cap of the Verpa mushroom looks like a small thimble or bell. It is small, averaging between 0.6-1.2 inches across and 0.8-1.6 inches in height. Its most important feature for identification is that the cap is only attached at the top of the stem. The edge of the cap hangs freely like a skirt or a lampshade. This is distinctly different from most true morels, whose cap edges are tight around the stem.

The cap surface ranges from tan to dark brown in color and is smooth or slightly wrinkled at maturity, depending on the species. The texture becomes tacky when wet.

Cap flesh is very fragile, and because the caps are only attached at the top, they are prone to breaking or falling off. You may find specimens without caps late in the season.

Verpa bohemica has a distinctly wrinkled cap that looks like a brain.

Verpa conica has a rounded cap that stays smooth until it ages or encounters dry weather. The cap of this species, and the whole mushroom in general, is generally smaller than V.bohemica.

Stem

The stems start cream-white to yellowish and darken with age. They might turn orangish when handled. The surface of the stem often has fine granules or scales that can form concentric belts.

They are mostly hollow but usually contain cottony pith that looks like cotton candy or pillow stuffing. This is another key that you’ve found a Verpa instead of a true morel. True morels are completely hollow inside. Unfortunately, this isn’t always reliable because with age, Verpa species may lose their cottony fibers and become entirely hollow.

Mature stems typically measure ½-1½ inches wide and 2½-8 inches long. They usually get wider at the base. Inside the stem, you’ll find cottony, wispy fibers that look like cotton candy – unlike true morels’ completely hollow stems.

The stems of both North American Verpa species are pretty much the same.

Smell and Taste

These mushrooms do not have a distinctive smell or taste.

Flesh and Staining

The flesh is whitish, thin, and fragile. The stem may stain orange when handled.

Spore Print

Verpa mushrooms have yellowish spore prints.

Key Identification Points

- Cap attaches only at the top of the stem

- Cap edges hang freely away from the stem

- Looks like a thimble or lampshade (always check where and how the cap attaches, aka the “thimble test.”)

- Stem is usually mostly hollow with some cotton-candy like fibrous material inside

North American Verpa Species

Verpa bohemica (syn Ptychoverpa bohemica in Europe)

Verpa bohemica has a wrinkled, ridged, or pitted cap, sometimes with brain-like folds. Verpa bohemica’s ridge tips sometimes have darker coloring.

Verpa conica

Verpa conica has a smoother, rounded cap that might show slight wrinkles as it ages or in dry conditions.

Verpa Mushroom Edibility

Verpa mushrooms are safe to eat when properly cooked, just like true morels. They are poisonous in raw form. As with all mushrooms, you might have an individual intolerance, and it’s always best to try just a little bit the first time to see if you have a reaction.

Verpa mushrooms taste mild and delicate, like true morels but lighter. They have a waxy feel, and the folds inside the stem hold juices, which means they can hold quite a bit of flavoring. The flesh is tender and will shrink down a bit with cooking because it is so thin.

These mushrooms should be cooked for 10-15 minutes to ensure they’re thoroughly heated and the toxins negated. French chefs often boil fresh verpas in stock or wine before frying them; this boiling beforehand is to make sure they are cooked completely.

Start with a small cooked portion (about 1 oz) and wait 12 hours to check for any reactions. No adverse effects means you’ll likely handle them well. Skip alcohol when eating verpas since some people report possible interactions.

Bad reactions to verpa mushrooms usually include upset stomach, nausea, vomiting, stomach pain, and temporary coordination problems. Some people might feel confused or dizzy, though this is infrequent.

The most common cases of poisoning are from eating too much in one sitting. So, even if you find these, be careful not to overindulge!

Verpa Lookalikes

Verpa vs true morels

The cap attachment is what sets verpas apart from true morels. True morels have caps that connect right to the stem with no gaps. Verpa caps hang loose from the stalk like a skirt or bell. True morels have caps with hole-like pits. The caps of verpas are wrinkled or have a ridged surface but aren’t pitted like morels.

To tell verpas from true morels, check the cap attachment first. True morels (except half-free varieties) have caps fully attached to the stem instead of hanging free. When you cut them in half, you can see another big difference. Verpas have cottony fibers inside their mostly hollow stems, while true morels are completely hollow inside. Half-free morels might look like verpas at first, but their caps attach halfway down the stem rather than just at the top.

Verpa vs. Half Free Morels (Morchella sp)

There are two true morel species that look a bit different from their relatives. These two species, Morchella populiphila and Morchella punctipes, are called half-free morels. They look a lot more like Verpas than the other morels because their caps are shorter in length. At a quick glance, the half free morels and Verpa bohemica, in particular, look almost identical.

But, there are some key differences with further inspection. The half free morels have very distinctive vertical ridges, like all the other morel species. V. bohemica’s ridges and folds are more rounded and brain-like. They are not sharp and so defined.

Another difference is the stem interior. Half free morels, like other morels, have hollow interiors. They will not be filled with a cotton like pith.

M. populiphila is found in western North America, while M.punctipes is from eastern North American.

Verpa vs Gyromitra (false morels)

Gyromitra species are nowhere near as safe—they contain gyromitrin, a toxin that breaks down into monomethylhydrazine when digested. Some people eat these after a pre-boiling treatment (make sure you know how to prepare Gyromitra before indulging in them!). These false morels usually have caps that look like brains and are a reddish-brown color. Like Verpas, Gyromitra species have a cottony fill inside them, but it is much more prevalent and thicker — very stuffed. The interior stems of Gyromitra are also often divided into chambers or sections.

Caution: Why the ‘hollow rule’ is unreliable

The “hollow interior” test isn’t enough on its own since both morels and verpas can look hollow. Verpa species may lose their cottony interior with age. You should check how the cap connects to the stem to be sure of what you’ve found.

Verpa Mushroom Medicinal Properties

Research has shown that Verpa bohemica has significant antibacterial activity, particularly against Escherichia coli. It has potential as a natural antibiotic compound. The antimicrobial compounds found in this mushroom have been used in traditional medicine practices, with studies confirming their effectiveness against certain pathogenic bacteria and fungi.

Common Questions About Verpa Mushrooms

What are the key differences between Verpa mushrooms (early morels) and true morels?

The main difference is in the cap attachment. Verpa caps are only attached at the top of the stem. They hang freely like a thimble or a bell. True morel caps are fused to the stem. Verpa stems also have a cottony pith inside them, while most true morels are completely hollow inside.

Are Verpa mushrooms safe to eat?

Verpa mushrooms are edible when properly cooked. They should never be consumed raw because they are toxic this way.

Where and when can I find Verpa mushrooms in North America?

Verpa mushrooms are typically found in moist environments near cottonwoods, willows, and aspens, especially along riverbanks with sandy soil. They appear in early spring, usually about a week before true morels. The exact timing varies by region.

How can I distinguish Verpa mushrooms from lookalikes?

Examine the cap attachment and interior structure. Verpa caps hang freely, and their stems contain cottony pith. Lookalikes like Gyromitra species (false morels) have brain-like, reddish-brown caps and solid or chambered interiors.

Can verpa mushrooms be cultivated?

Verpa mushrooms have not been commercially cultivated with the same success as true morels (which is also a pretty recent development). Their cultivation challenges mirror those of true morels, which were considered nearly impossible to grow reliably until recent breakthroughs. Verpas are primarily foraged in the wild.

Lee says

I found this really strange looking mushroom and I’m wondering what it is

Jenny says

You can submit photos to our facebook group. Make sure to read the guidelines first before posting https://www.facebook.com/groups/340690111324762