The Dyer’s Polypore, scientifically known as Phaeolus hispidoides (Phaeolus schweinitzii), is a parasitic fungus that is common in conifer forests around the world. It also has a rich history tied to the textile industry. Its common name, “Dyer’s Polypore,” stems from its historical use as a natural dye source for coloring yarn and fabrics.

The English language is often very confusing. So, to be clear, we are talking about dyeing and NOT dying. One letter in a word can really change its meaning!

- Scientific Name: Phaeolus hispidoides aka Phaeolus schweinitzii

- Common Names: Dyer’s Polypore, Velvet Polypore, Dyer’s Mazegill, Velvet Top Fungus, Pine Dye Polypore, Cowpie Fungus

- Habitat: On living or dead conifer trees

- Toxicity: Non-toxic, inedible

Jump to:

All About Dyer’s Polypore

For centuries, people have harnessed the vibrant pigments present in various mushrooms to color textiles. Among these mushrooms, the dyer’s polypore was a prized species due to its impressive color range and dyeing properties. The fruiting bodies of this mushroom were used to dye yarn various shades of yellow, orange, and brown, depending on the age of the fruitbody and the type of mordant used to bind the dye molecules to the fabric fibers. This mushroom’s rich, earthy hues were prized by textile artisans. In the 70’s and through today, mushroom dyeing made a comeback that is still strong.

Dyer’s polypore is parasitic on the roots of coniferous trees, mainly pines, spruces, and occasionally larches. It can kill its host tree through root and butt rot, turning saprobic to feed on the dead roots and stumps once the tree topples or is felled.

The scientific name, Phaeolus schweinitzii, honors American botanist-mycologist Lewis David von Schweinitz, who is often considered the founding father of North American mycological science. The genus name Phaeolus translates to “somewhat dusky” or “darkish,” a reference to the mushroom’s typically dark coloration.

Identifying the Dyer’s Polypore

Season

The fruiting season of the dyer’s polypore is from late summer into fall and sometimes early winter. It can persist throughout the year under ideal conditions.

Habitat

The dyer’s polypore prefers pine and Douglas fir trees, but it can also appear near other conifers. While it primarily grows on the ground from the roots of these trees, it can occasionally be found on decaying stumps or slightly further up the base of a tree. It is more likely to appear on the tree trunk if there is a wound there.

This fungus is widely distributed throughout Europe, North America, Central America, Asia, and Oceania. In the United States, dyer’s polypore is commonly found on Douglas fir in the West, white pine in eastern North America, and loblolly pine in the South.

Dyer’s polypores usually grow individually but can also grow in clusters. If there is one, there are often a few others nearby. It often looks like they are growing from the ground, but they are actually attached to the tree roots underground.

Identification

Cap

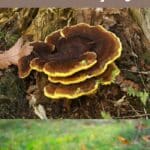

Dyer’s polypore is composed of several circular to irregularly lobed caps gathered together to form an irregular circular or semicircular rosette-like structure. The center is either flat or slightly sunken. The caps grow up to 10 inches in diameter. When fresh, the flesh of the cap is soft, but it becomes tough with age. The surface of the cap is densely hairy (velvety; this is where the common name velvet cap originates) when young; it often smooths out with maturity, losing the velvety texture.

The color of the cap is variable. It ranges from cream to ochraceous, yellow, or green-yellow when fresh and transforms into rusty brown to dark brown as it ages. It is usually much lighter, brighter, and more distinctive when young, often with a deep golden-yellow color.

The colors appear in concentric zones on the cap surface, usually with the edge being much lighter and more attractive. Very old specimens are usually entirely dark brown to black and look nothing like the younger specimens. They are bland or dull-looking at this point and often go unnoticed because they blend into their surroundings and don’t look that interesting.

The cap stains brown to black when touched. The flesh of the cap starts as yellowish-brown but darkens to a rusty brown as it ages.

Pores

Dyer’s polypore has a pore surface that extends down the stem. When the fungus is young, the pores are yellowish or orange and often quite brightly so. With age, the pores change to greenish, then rusty brown.

Stem

The stem of the dyer’s polypore is stalk-like and may be branched or unbranched, central or off-center, and sometimes even rooting. There is a lot of variance with the stem; sometimes, there is no discernable stem at all. It measures 1/4″-2″ long and is brown. Below the pore surface, the stem is velvety. It bruises a darker brown when handled.

Flesh and Odor

The flesh of the dyer’s polypore is initially soft when fresh but becomes tough as it ages. It often appears zoned, displaying different shades of brown.

The odor can vary, sometimes having a sweet fragrance while other times being relatively odorless.

Spore Print

The spore print is whitish or yellowish.

Dyer’s Polypore Lookalikes

Wooly Velvet Polypore, (Onnia tomentosus)

This fungus looks similar and also grows on the ground near conifers, most often spruce trees at high elevations. However, it lacks the bright yellow or orange colors in young stages. It is light tan to buff colored, but can develop some dark sections. It never has the yellow, though. Also, it’s pore surface is white or grayish, not yellowish.

Oak Heart Rot Fungus (Inonotus dryophilus)

This is another parasitic butt rot fungus that infects trees. It looks similar in color to dyer’s polypore, but it grows hoof-shaped on the side of trees. And, it attacks oaks, not conifers.

Chicken of the Woods, (Laetiporus sulphureus)

Chicken of the Woods is yellow-orange all over and more often grows above the root system of hardwood trees. It grows as shelves or rosettes and is easily differentiated by its bright coloring and growth habit.

Edibility and Culinary Uses

Dyer’s polypore is inedible due to its tough, leathery texture when mature. It also is quite bitter. However, it is not toxic.

Medicinal Properties

Research on the medicinal benefits of dyer’s polypore is limited. Some anecdotal evidence suggests that the mushroom may possess antimicrobial or anti-inflammatory properties, but further scientific studies are needed to confirm these claims.

Textile Dyeing With The Dyer’s Polypore

The use of lichens, minerals, plants, and mushrooms in dyeing fabrics dates back centuries. Dyer’s polypore was one of the common fungi used for dyeing clothes and yarn because of its rich pigments and available color spectrum. In North America, some Indigenous tribes used this fungus to create yellow, brown, and green fabrics.

Another reason this mushroom was used so much in dyeing is because it is widespread and easy to find in significant quantities. Many other valuable dye mushrooms are less common and harder to source. But not dyer’s polypore; this one is all over the place, and so, sometimes, by default, it became a top choice for dyeing fabrics.

In the 1970s, the artist Miriam Rice started experimenting with natural dyes from mushrooms, trying out every fungus she found. This led to a real mushroom dyeing renaissance, including conventions held around the world, the International Mushroom Dye Institute, and several books.

The dyeing process with dyer’s polypore involves extracting the pigment from the mushroom and applying it to the fabric. The resulting colors can range from vibrant yellows to rich greens, depending on the age of the mushroom and the mordant used in the process. Young specimens produce yellows, while older ones give off more brown coloration. There are so many options, too; dry mushrooms create different color schemes than fresh ones. And how long you soak the fabric greatly impacts the final color.

This step-by-step guide is a great place to start if you’re interested in learning more about dyeing with the dyer’s polypore. This video tutorial is also excellent! This compilation of the Best Mushrooms for Color, unsurprisingly, lists dyer’s polypore first.

This is an excellent dive into the history of dyeing with lichens.

Landscape Management: Butt Rot Infected Trees

The dyer’s polypore causes a brown cubical rot in the heartwood of the butt and roots of living conifers. This rot can lead to significant structural weaknesses in trees, making them susceptible to wind storms and other forms of damage. Foresters and arborists employ various landscape management strategies to mitigate the impact of butt rot on tree health and stability.

One common approach is to identify and remove infected trees to prevent the spread of the fungus to healthy individuals. The fungus spreads from tree to tree through spore dispersal and also underground mycelium reaching out to new trees. Proper pruning techniques can help reduce the risk of windthrow by maintaining a balanced canopy structure.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to know a tree is infected until you see the fruiting mushroom body. And, by then, the infection has spread quite far. There is no way to reverse or kill off the fungal infection – the infected tree cannot be saved. But, trees with butt rot from the dyer’s polypore can potentially live many years with the infection.

Management Strategies

- Keeping trees healthy is crucial in preventing and reducing the impact of dyer’s polypore. Proper tree care practices, including adequate watering, regular pruning, and appropriate fertilization, can help enhance tree vigor and make them more resilient to fungal infections.

- Maintaining a diverse forest ecosystem with a mix of tree species can help reduce the risk of widespread dyer’s polypore infections. Planting a variety of tree species creates a more resilient forest that can withstand the impact of this fungus.

- Regular monitoring of trees for signs of dyer’s polypore infection is essential. If infected trees are identified, prompt removal and appropriate disposal can help prevent the spread of the fungus to healthy trees.

- Implementing good forest management practices, such as thinning overcrowded stands and promoting proper spacing between trees, can reduce the risk of dyer’s polypore infections. These practices improve airflow and sunlight penetration, creating unfavorable conditions for the fungus to thrive.

Common Questions About Dyer’s Polypore

Is Dyers polypore toxic?

No. This is a nontoxic yet inedible fungus. The flesh is too tough to eat.

Can you eat Dyers polypore?

It is not palatable, It has a tough, woody texture that makes it not fit for eating.

Doug Adams says

I really appreciate the depth of your description of Dyer’s Polypore. I’ve never heard of it nor seen it. I’m in Temagami, north eastern Ontario, just an hour north of North Bay. A follower of my mushroom site forwarded a pic of what she found in her yard an hour north of here in Englehart and the pics are at least very similar if not exactly what your pics are. I found a difference in her pics and yours is the timing of growth. You say late summer and she’s taking pics now in early July. If you’d like to see my site of at least a couple hundred or more different mushrooms, go to http://www.northland-paradise.com and click on the mushroom page that I started probably 15 or 20 years ago or more. I even have a few “unknowns” for the first few pics that I cannot identify. Any assistance here would be greatly appreciated. Keep up your good work with fungi. I’ll certainly keep an eye open around here for examples of this one as there are lots of conifers in this part of Ontario.

Jenny says

It could well be dyer’s polypore. In the seasonal information, I explain “It can persist throughout the year under ideal conditions.” It is an annual mushroom mushroom in many places (meaning it persists all year round). And, with the super mild winter we just had, maybe this one is from last year or got an early start. You can post pics on our facebook page for any unknowns — make sure to read the pinned/featured post and include all the relevant info and pics. Happy mushroom spotting!